The meaning of Nakba Day

Reading a seminal manifesto of Arab nationalism

Tomorrow is Nakba Day, an official annual event since Yasser Arafat inaugurated the day in 1998. It is an important day for Arabs all over the world, since the legacy of the Nakba (often translated today as “the Catastrophe”) is a foundational pillar of Arab nationalism. In a limited sense, the day commemorates Israel’s displacement and dispossession of over 700,000 Palestinians, and Israel’s appropriation of dozens of their villages, during the first Arab-Israel War (1947-1949). However, the meaning of the Nakba, and therefore of Nakba Day, extends far beyond that. In its most essential and broadest sense, the Nakba refers to the ongoing threat that Zionism allegedly poses to Arabs throughout the Middle East and the world.

The significance of the phrase “the Nakba” can be traced back to a single book, entitled Ma’na al-Nakba (published in English as The Meaning of the Disaster). Written by Constantin Zurayk, the book draws on the experiences and stories of the war to forge a powerful manifesto of Arab nationalism. Perhaps no single book, apart from the Quran, has been more influential in shaping Arab consciousness. It was originally written and published in Beirut in 1948, during a pause in the hostilities. It sold out so quickly that a second Arabic edition was published that same year. The English-language version was published, again in Beirut, eight years later.

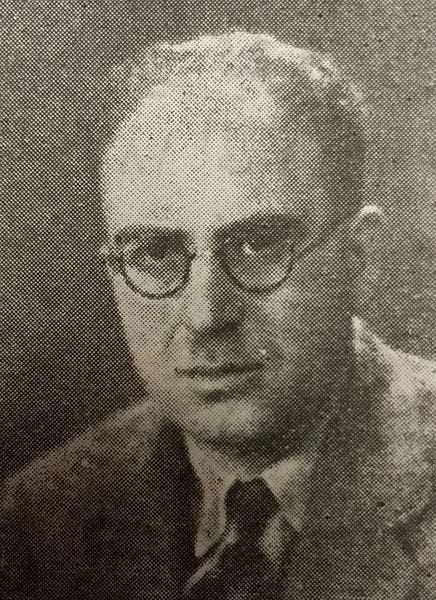

Born in Damascus to a Greek Orthodox Christian family, Zurayk was an influential Syrian professor, author, and UN delegate, with doctoral degrees from both Princeton (1930) and the University of Michigan (1967). Known academically for his secularism and rationalism, his lifetime of devotion to the Arab cause earned him the title, "father of Arab nationalism."

Though neither his first nor his last work to shape the nascent Arab national consciousness, Ma’na al-Nakba has probably had the most profound and lasting impact of any of them. It is therefore an essential text for understanding both the origins of Arab nationalism and the role of the Nakba as a narrative frame of Arab national consciousness.

To put the book in historical context, we must remember that Arab nationalism (or Pan-Arabism) was not yet an entrenched worldview. When Ma’na al-Nakba was published, it was only just starting to become a widespread idea in the region—and, indeed, in the world. This explains why Zurayk makes a protracted effort to promote both a sense of and a belief in the need for Arab unity. At the risk of belabouring the point, let me emphasise that the book is not about Palestinian nationalism at all. It is about Arab nationalism.

This is clear from the very first sentence, which reads, “The defeat of the Arabs in Palestine is no simple or light, passing evil”(p. 2). Seven pages later, he again refers to “the Arabs of Palestine,” and never to Palestinians. Similarly, the seven states which declared war on Israel (Syria, Transjordan, Lebanon, Iraq, Egypt, Saudi Arabia & Yemen) are all regarded as “Arab states,” and every effort is made to regard them as a single national force. This is intentional, as we will see.

If the English-language version is any indication, Zurayk wrote plainly and powerfully, so that there could be little doubt as to his intentions and aims. He draws on his audience's emotions—especially fear and anger—to focus their hearts and minds on a singular goal: the formation of a stronger, more formidable Arab nation. That is what the meaning of the Nakba is: the need for an Arab nation that can overcome its greatest obstacle: Zionism.

The book is at once a criticism of Arab disunity and unpreparedness and a crusade for Arab strength and unity in the face of a worldwide Jewish conspiracy. He uses the word “crusade” repeatedly to describe his efforts, using collective pronouns to include all Arabs in the movement. Zurayk hopes that the “violent shock” of the Arab loss will “return us to reality, and rouse us to the facts of the situation, and help us properly to assess the matter and to make provision for it”(p. 5). The situation, he explains, is “a long war” over the existence, and also the expansion, of Zionism in the Middle East (p. 7). He pleads not only for justice for Arabs immediately affected by Zionism, but for the future of all Arabs all over the world.

Zurayk’s conception of Zionism is clear: It is a global monstrosity that involves “the Jews of the whole world”(p. 7) He personifies Zionism, saying, “He extended his influence and his power to the ends of the earth”(p. 4). He goes on to claim that Zionism “is a worldwide net, well prepared scientifically and financially, which dominates the influential countries of the world”(p. 5). He later explains, “In recent years this power has been centred in the United States. No one who has not stayed in that country and studied its conditions can truly estimate the extent of this power or visualize the awful danger of it”(p. 65).

Regarding Jews in such conspiratorial terms was not new. It has been a common trope of antisemitism since the 19th century. It was behind the infamous forgery, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion (1903), and it persists today in various forms, such as Holocaust denialism. It is therefore unsurprising that the threat of a global Jewish conspiracy would be a central tenet of the budding Arab nationalism. Indeed, Zurayk does not seem to feel any need to justify his claims about a global Jewish conspiracy at all. The fact of such a conspiracy goes without saying. He is thus able to speak about “expansionist Zionist power and rapacious greed” (p. 32) and “Zionist evil” (p. 34) repeatedly, with confidence and authority, and without evidence.

Though he observes that “the topic of Zionism and its evils are on almost every lip and tongue,” Zurayk wants to “strengthen the sense of danger”(p. 14). This, he says, is the first of five principles of his crusade for the Arab nation. He therefore refers to “the great danger which Zionism represents for every country in the Arab world,” claiming that his readers still “have not perceived the true extent of Zionism, its world-wide strength, its goal of conquest and annihilation, and its naked cruelty in realising this goal”(p. 14). He credits Nazism with “saturating” the “hidden yearning in the breasts of Jews . . . to found their own state in Palestine”(pp. 14-15). He refers to the Jewish dream as “imperialism, naked and fearful, in its truest color and worst form”(p. 15). His rhetoric takes on mythic proportions when he says, “the Zionist danger is the greatest danger to the being of the Arabs,” and that it alone “threatens the very center of Arab being, its entirety, the foundation of its existence. All other [dangers] are simple in relation to it and may, for the sake of repelling this most serious and all-important danger and for the sake of preserving one’s self from it, be endured, or at least have their solution postponed”(p. 16). Zurayk portrays the essence of the Arab identity in a mortal struggle against the mysterious yet ever-present Zionist enemy.

This is obviously and intentionally propaganda—which Zurayk thought was necessary for the Arab crusade. He says that “domestic propaganda” is what is needed most for the “mobilisation of feeling and will,” “so that every thought we have and every action which we perform will be influenced by this feeling and will issue from it,” in order to manifest “the struggle of one ready to die”(pp. 16-17). Without such propaganda, and without the will to die for the cause, he warns that Arab states will not be able to defeat Zionism.

The second of the five principles is “material mobilisation in all fields of action”(p. 17). He says the Arab nations must “recognize the abundance of Zionist resources and the awe-inspiring financial and political forces which support them”(p. 17). He also calls on the recruitment of the entire civilian population for war: “War today has become total war, not confined to the troops in the field of battle, but involving all the people; not content with some of the resources of the nation, but demanding the mobilisation of them in their totality”(p. 21). He even argues that Arab states should “halt projects for reform and for building up our countries internally,” and that states may “have to divert to the war effort appropriations for public works, education, and agriculture, in fact all the income of the Arab states—above the minimum necessary for living”(p. 21). When looking at Gaza today, we must ask: Did Zurayk directly influence Hamas’ decision to keep the Palestinian population at the poverty line by appropriating as many resources as possible for military purposes? And did Zurayk directly influence Hamas’ decision to institutionalize the recruitment of child soldiers and to militarize as much of civilian life as possible?

The third principle of his crusade is political unification, which is all-encompassing and almost spiritual in scope. He explains it forcefully: “I have said that this unification which we seek in the fields of war, politics, economics, propaganda, etc., is linked to the circumstances and present situation in the Arab states and that unification cannot rise above the level of this situation. Unification is the consequence and the fruit; the existent Arab being is the determinant and the root”(p. 24).

Zurayk’s fourth principle is related to the second: it is “the participation of popular forces,” meaning that “all classes of society” and “every individual in the nation” will be involved in the war against Zionism (p. 25). He says, “The struggle must not be limited to governments and regular armies”(p. 25). So again we have the injunction that the entire Arab nation, and all of its members, must become soldiers, be they regular or “irregular”—meaning unofficial and informal civilian soldiers.

Finally, he says that Arabs must be ready “to bargain and to sacrifice some of their interests in order to repel the larger danger,” and that “the primary interest of the Arabs in this stage of their history is to protect their existence from Zionist danger”(pp. 27-28). This can be read as a word of practical advice: be ready to give up some personal wants or needs for the sake of the greater good. However, it is much more than that: for it is not simply the greater good that Zurayk is appealing to. It is their very existence. In that sense, this principle is not merely about practical interests. It is about understanding that the existence of the individual Arab depends upon their commitment to the nation; that the greater good is the good of the individual, and must replace the perceived interests of any particular individuals. So he says that Arabs “should not be motivated by feeling, ‘traditional friendship,’ or ‘natural alliance,’ for in most cases these are only snares and traps which conceal greed and mask exploitation and colonization”(p. 28).

After laying out the five pillars of the Arab crusade against Zionism, Zurayk begins a chapter entitled “The Fundamental Solution,” and his writing style becomes downright oratorial. On page 35, he raises the parallel questions of an “Arab fatherland” and an “Arab nation” with rhetorical sophistication:

I wonder whether it is right for us to say that there is an Arab fatherland. If we mean by fatherland simply the mountains and rivers, the plains and shores, there is no doubt that it has existed ever since the Arabs settled in their present abode. However, if—as is meet and right—we mean the permeation of the meaning of the fatherland into the Arab mentality, the birth of the will to defend and exalt it and to forward its progress, then the answer is no!

Another question: Is there an Arab nation? If we mean by a nation a people who speak the Arabic language and who possess the potentialities for becoming a nation, then the answer is in the affirmative. However, if—as is meet and right—we mean by this word a nation which is united in its aims, which has actualised its potentialities, which looks forward to the future, and which opens its eyes to the light and exposes its breast to the good, whatever the source of the light and the good, then the answer is no!

He contrasts the Arabs with the Jews, who (he claims) “did not have a fatherland in the first and natural meaning of the word”(p. 35). This of course denies the historic reality of the united Kingdom of Israel and, later, the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah. It replaces history with the idea that Zionists “have woven together a dream which they have resolved to realize, and which they have already gone a long way towards realising, in a land which is not theirs”(p. 36). In addition to lacking a legitimate claim to any land, Zurayk claims that Jews do not even comprise a nation, “for they are from widely separated lands, speak different languages, and follow different ways. Their only common bonds are religion and suffering”(p. 36). On this basis, Zurayk claims that Arab nationalism is “natural,” while Zionism is “unnatural”(p. 36).

From a rational point of view, Zurayk’s argument is deeply flawed. Jews share a common history which is centred on a national language—Hebrew, which is the official language of Israel—and Jewish identity involves a family of shared values and practices. On the other hand, Zurayk is building a united Arab consciousness that lacks a shared religion. Zurayk’s family is Christian, though the majority of Arabs are Muslim. We must wonder if Zurayk would have included Arab Jews in his idea of an Arab nation. He does not mention them at all. The point is, the Arab people have no more natural claim to land than the Jews, and the Arab people also enjoy a heterogenous family of values and traditions. By calling one nation “natural” and the other “unnatural,” Zurayk is abandoning scientific rationalism for the sake of propaganda. He is defining the Arab national identity as a political being whose raison d'être is to defeat the evil and unnatural Zionist Other.

Later on, in a more prosaic supplement to the main text, Zurayk does address the actual history of Jews in the region of Palestine, though again he applies a double standard. He says Jews are not indigenous to the region, because they “infiltrated Palestine in ancient time as other Semitic tribes infiltrated the countries of the Fertile Crescent”(p. 60). Of course, it was not called “Palestine” then. In any case, if having a “natural” right to a land requires that one not have come from tribes that originated elsewhere, then no Arab would have any rights to Palestinian land, either.

Perhaps Zurayk realises this, because he then argues that appeals to history are irrelevant anyway: “If historical relationship is a valid basis for claiming title to a country, the Arabs would today have the right to claim Spain, the Italians would have the right to claim England, and all the population of the United States would have to leave it and return it to the American Indians”(p. 61). Without arguing the historical issues that he raises, we must again wonder what argument this could serve. He is undermining his own claim that the Arab nation has a natural right which justifies their rejection of a Jewish homeland in Palestine.

Zurayk is well aware that the conflict began when Arabs in Palestine denied Jews the right to build a national home in Palestine. He says this explicitly at the beginning, on page 3. His eventual argument is that the Arab’s had nothing to do with Jewish suffering and cannot be blamed for any of the problems that have befallen the Jewish people; and therefore, that Arabs should not be burdened by the Jewish problem.

This attitude denies that Jews suffered any oppression or unfair treatment under Ottoman rule. It also ignores the ways that some Arab leaders collaborated with and even emulated the Nazis after the Ottoman Empire fell. Quite ironically, Zurayk claims that the only way to solve “the worldwide Jewish problem” is through religious tolerance (p. 72). If he were so interested in religious tolerance, then why is he so against the existence of a Jewish national home in Palestine? Why does he demonize Jews in such absolute and unforgiving terms?

I will not here go into the historical and political facts that have shaped the ongoing conflict between Israel and the Arab world at large. I will not at this time discuss what happened that led over 700,000 Arabs to become displaced and dispossessed. There has been a great deal of propaganda and misinformation about the history, so that the basic facts of the Nakba remain contentious. I will not address that today.

What I hope this excursion has demonstrated is that the ongoing conflict between Israel and Palestinians is of the most profound importance to Arab consciousness in general. It is not simply about the lives of Palestinians, but about the identity of the Arab nation. The struggle for Palestine has held a symbolic importance for Arab national identity since its modern inception. And throughout that time, the meaning of the Nakba has projected the deadly image of a greedy, shadowy, global Jewish conspiracy to annihilate the Arab world.

Respectfully recommend you consider reading TOWARD NAKBA AS A LEGAL CONCEPT,

Rabea Eghbariah, Columbia Law Review, VOL. 124 NO. 4